Contextualizing Reemergence of Polio in Pakistan

Exploring Impacts Socio-cultural Perceptions, (Geo-)Politics, COVID-19, and Floods

Abstract

Pakistan has reported a significant increase in polio cases from 2019 onwards. Despite massive global efforts, what has gone wrong with a mega initiative of polio eradication, especially in Pakistan? During July 2022, media reported the “fake” finger marks on children’s fingers to show that they are vaccinated. Hence, it is important to ask: Why people refuse and resent vaccination? If people accept western medicine, then why they cannot accept the vaccination that has roots in biomedicine. The article asks for ethnographic research that should thoroughly study and analyze polio.

Introduction

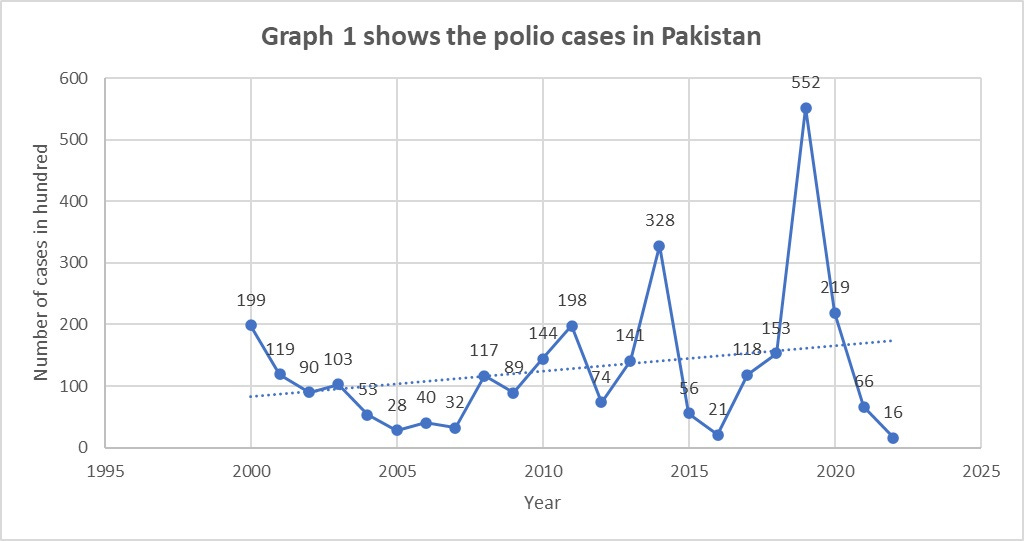

Polio is a deadly but preventable disease. Its prevalence anywhere poses a danger to everywhere, because the virus is highly contagious, which spreads stealthily. Although 99% cases have dropped due to the World Health Assembly’s Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) that started in 1988, eradicating 1% has emerged as a mammoth challenge [1]. For the first time, the advocates of the polio initiative are admitting that the success to eliminate polio is still far away, and they are debating how to tackle this emerged stalemate [2]. The virus still appears a great challenge. It is still prevalent in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Although Nigeria was also among polio prevailing countries [3], the recent reports show no polio cases from the last three years [4]. Presently, all eyes are on both countries. In 2019, Pakistan topped with around 552 cases, while Afghanistan reported around 90 cases (see Graph 1) [5, 6].

COVID-19 Challenges Polio Eradication

The infection has increased during 2020-2022 due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This is because vaccination activities were halted [7]. Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) estimated that almost 80 million vaccination opportunities have been missed by children in the Eastern Mediterranean Region as a result of the recent pandemic [7]. Pakistan resumed a limited-scale polio vaccination campaign on 20 July 2020 after a four-month suspension of all polio vaccination activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic [7].

However, parents seemed hesitant and scared due to COVID-19, whether they can leave their homes and to take their children to the basic health facility for vaccination. Some people refused the polio vaccine whilst believing that it would do no good to their children: Ali and colleagues mention the views of one respondent as follows: “As soon as the vaccination team arrived here, we promptly asked them not to vaccinate our children and return because they have been vaccinating our children for a long time. Yet, the health of our children does not improve. Many of them remain sick. Given that, what is the purpose of having our children vaccinated?”[8]. In the same village, laypersons also perceived “coronavirus's spread to be a “Western production,” and the vaccine is a product of the Angraiz (British), thus, “Who knows what types are these vaccines, and what if we allow vaccinators to vaccinate our children and then our children die?”[8]. Hence, rumors, fears, misconceptions as well as socio-cultural (geo)political, and religious factors have simultaneously contributed to vaccine hesitancy and refusal among various communities of Pakistan [8].

Consequently, the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) drop off was a 26% average decrease throughout the lockdown period, especially in March 2020 compared to pre-lockdown period of COVID-19 [7]. According to Pakistan Polio Eradication Program, poliovirus was detected in 60% sewage environmental sample in August 2020 while it was 43% in August 2019. There is a marked increase over the last year that might be a future concern. In 2020, there were 84 wild polio virus (WPV) reported cases across the country and the cVDPV2 polio cases were 135 [7]. However, the cases reported from other sources were 455 [5]. The cases have also been reported in 2021 (8 WPV and 1 cVDPV2), and 2022 (11 WPV and 0 cVDPV2) (see Table 1).

Table 1 Shows cases of polio during last four decades

Why does polio still prevail in Pakistan?

This reemergence of polio raises serious concerns as despite many efforts at various levels, the virus is still causing cases. Since effective global vaccination has eradicated polio serotypes 2 and 3 around the world, type 1 serotype (WPV 1) polio infection is still prevailing in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The failure of eradication in Pakistan means a failure of an over 25-year-old polio initiative that coasted around $10 billion [9]. The wild poliovirus has not been interrupted in Pakistan [10]. Hence, a worth raising question is why polio prevails in Pakistan despite massive efforts at the national and global level?

The Politics of Vaccination

The factors that affect this global initiative are multiple: social, political, and management-related [11]. The significant reasons encompass religious, politics, awareness-related insecurity, inequity of resources, governance, and social responsibility [12].

There are many who believe that sociocultural factors play a decisive role in parental refusal and resentment. However, how people can reject the vaccination, when they do not reject or resent biomedical care; western dress pattern; English language; travelling by air, bus, and train; lighting houses with electricity; holding mobile phones; using televisions. Instead, most people prefer them. For instance, people give value to English than their native language. As if someone speaks excellent English with a British/American accent, the individual is considered as educated and wise. There are numerous inventions – that I have mentioned randomly – which occurred in the western world, but we are proudly using them. Hence, in a society where other ‘western’ values and inventions are preferred and practised, what is wrong with vaccination? Such underlying reasons have seldom adequately been interpreted and incorporated into the strategies.

Hence, the reasons related to (geo)politics are substantial. Of these reasons, the high level political and official commitment has improved over the years, but the district level commitment is still lacking [13]. An ‘office politics’ exists at a district level, where employees resist the superiors’ directives in numerous ways such as refusal to work, falsification of data, corruption, false compliance, and confrontation [11]. This politics can be due to an insufficient pay to such staff and imposition of “international mandates” as a vaccinator receives around $2.00 per day, while the WHO’s consultants receive around $10,000 per month with other facilities [11].

The engaged stakeholders negotiate polio to meet specific ends. The negotiation occurs at several levels, but just different in terms of type and scale. In 2022, the media recently reported about a leader of a traders’ body in the Bannu region from Khyber Pakhtunkhuwa province, who announced to boycott the vaccination drive if the government opts not to withdraw specific taxes. In 2022, Dawn newspaper wrote an editorial how parents used “fake marks” on their children’s fingers to create evidence that these children are vaccinated.

Vaccination and Geopolitics

Another vital aspect, people label vaccination as ‘Western plot’ to sterilise Muslims and see some ‘hidden interests’ beyond it [14]. This labelling became further dominant after a revelation that the US Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) used a ‘fake’ hepatitis vaccination in Pakistan’s Abbottabad city to locate the Osama bin Laden [12].

Thus, conspiracy theories and rumours have surrounded the vaccination program in Pakistan. In April of 2019, media reported a man in Peshawar spread misinformation about the polio vaccine, asserting that it caused children to faint and die. After the rumour, a mob attacked a government health facility and murdered a woman polio worker in Chaman city of Baluchistan province. These assaults resultantly compelled the government to halt the scheduled polio vaccination drive across the country due to safety concerns about 270,000 polio workers.

This perception, perhaps, is the reason for the abduction and deaths of polio teams across the country. The news floated in 2013 about the abduction of 11 teachers and the killing of four law enforcement officers providing security to vaccination team in KP. Since 2012, over 100 such attacks have been reported in the country, killing over ten dozens of vaccinators, escorting security and other citizens [12].

Polio and Disasters: The Case of Flood 2022

Outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs) follow complex emergencies, and natural disasters: e.g., floods, tropical cyclones (e.g., hurricanes and typhoons), tsunamis, earthquakes, and tornadoes [15-17]. The major causes include the shift of resources (particularly overstretching of health-related sources), a large-scale population displacement and crowding, a dearth of basic needs such as food and clean water, poor hygiene and sanitation [18]. Preventing communicable diseases need a proper follow-up of vaccines. But during natural disasters it becomes difficult to provide people with a necessary primary healthcare service, encompassing continue vaccine campaigns.

The same is expected in the current flash floods in Pakistan, especially in its two provinces: Sindh and Balochistan [19]. The continuous monsoon rain has resulted in floods affecting many houses, which have either fallen or about to fall. According to my rapid research in Sindh province, several villages are under water. Around 80% of the population of each village has been displaced. In one village located in Khairpur district, several private schools have been converted as flood camps where hundreds of people live together. Moreover, crops have been ruined; the livestock is dying. All this sudden change is causing critical effects on people’s mental and physical health. It is not possible for people to maintain hygienic practices. They do not have access to healthcare services, and they do not have sufficient food to eat.

On the one hand, unhygienic practices, lack of food and great interaction among people will make them vulnerable to be affected by VPDs including polio. On the other hand, it is not possible for the government to continue scheduled vaccination drives due to shifting of resources and problems caused by floods to reach specific areas and dislocated people.

Challenges Posed by Polio: National and International

This rife of polio poses challenges for Pakistan, both domestically and internationally. Domestically, since polio is a highly contagious disease that spreads rapidly, the challenges will be socio-cultural, economic, and political. Polio will paralyse more children, augment the miseries of people, and increase the burden of disease. Tackling it creates the necessity to devise policies and practical measures to meet the needs of affected persons for their smooth and productive survival.

Internationally, the challenges have strong associations with foreign policy. For example, according to the media, in November 2013, polio cases identified in Syria were linked to a virus having Pakistani origin. Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a polio emergency in Syria. Similarly, reports exhibited that the origin of polio cases identified in China, Alazhar University, Egypt, and Palestine during January 2012, December 2012, and March 2013, respectively, were also traced back to Pakistan [14].

Such cases and links hint at the risk that other countries fear. For avoiding risks, other countries may put a travel ban on Pakistani going abroad. At the beginning of this decade, Saudi Arabia already showed its intention about the travel ban, and India already made it necessary for Pakistani travelers irrespective of age to prove the vaccination [14].

Certainly, polio is not a solitary deadly infectious disease to determine such decisions, but other contagious diseases, such as measles, hepatitis, and the alarming rise of HIV/AIDS, will also play their part now.

Conclusion

Since polio is no more a local issue, but a global. The polio problem needs a thorough revision of the whole paradigm of eliminating polio at all levels: global, national, and local. There is a need to be more aware of the power dynamics that can hinder or help in polio’s elimination.

For understanding the problem of polio, conducting ethnographic and multidisciplinary studies on polio are necessary, as the country has a diverse population. The study should center on the local perception about polio and vaccination that is prevailing across the country, why does polio as yet prevail; and which way would be more appropriate to eliminate it? More significantly, researchers should explore the experiences of polio-contracted people and their families for developing awareness campaigns. Such studies would help address other infectious diseases, too.

The political will at a national level also plays a pivotal role to deal with any calling, including eliminating polio. For showing that, will, media have reported in August 2019, a crucial decision of the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan, to be a polio ambassador to spearhead the anti-polio program. The step exhibits the increase in political will. This step would improve the image of the highly cited phrase in the global discourse about Pakistan, ‘the political will.' These steps are indispensable and badly needed, especially by the concerned, influential, and accountable stakeholders to own the issues and play their due role in making our homeland problem-free.

References

1. Larson, H.J. and I. Ghinai, Lessons from polio eradication. Nature, 2011. 473: p. 446.

2. Roberts, L., Polio eradication campaign loses ground. Science, 2019. 365(6449): p. 106-107.

3. Ado, J.M., et al., Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication in Nigeria. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2014. 210(suppl_1): p. S40-S49.

4. Khan, F., et al., Progress toward polio eradication—worldwide, January 2016–March 2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2018. 67(18): p. 524.

5. WorldHealthOrganisation. List of wild poliovirus by country and year. 2022 N/A [cited 2022 August 27]; Available from: https://polioeradication.org/polio-today/polio-now/wild-poliovirus-list/.

6. World Health Organisation, Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: Monitoring System 2017 Global Summary in Incidence Time series for Pakistan (PAK) 2017, WHO.

7. Pakistan Polio Eradication Programme, Polio Cases in Provinces. 2022, Pakistan Polio Eradication Programme Pakistan.

8. Ali, I., S. Sadique, and S. Ali, COVID-19 and vaccination campaigns as “western plots” in Pakistan: government policies,(geo-) politics, local perceptions, and beliefs. Frontiers in Sociology, 2021. 6: p. 608979.

9. Roberts, L., Fighting Polio in Pakistan. Science, 2012. 337(6094): p. 517-521.

10. Alexander, J.P., Jr, et al., Progress and Peril: Poliomyelitis Eradication Efforts in Pakistan, 1994–2013. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2014. 210(suppl_1): p. S152-S161.

11. Closser, S., Chasing polio in Pakistan: why the world's largest public health initiative may fail. 2010, Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

12. Ali, I., Constructing and negotiating measles: the case of Sindh Province of Pakistan. Vienna: University of Vienna, 2020.

13. Ahmad, K., Pakistan struggles to eradicate polio. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2007. 7(4): p. 247.

14. Mushtaq, A., et al., Polio in Pakistan: Social constraints and travel implications. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 2015. 13(5): p. 360-366.

15. Culver, A., R. Rochat, and S.T. Cookson, Public health implications of complex emergencies and natural disasters. Conflict and health, 2017. 11(1): p. 1-7.

16. Watson, J.T., M. Gayer, and M.A. Connolly, Epidemics after natural disasters. Emerging infectious diseases, 2007. 13(1): p. 1.

17. Waring, S.C. and B.J. Brown, The threat of communicable diseases following natural disasters: a public health response. Disaster Management & Response, 2005. 3(2): p. 41-47.

18. Ali, I., Impact of COVID-19 on vaccination programs: adverse or positive? Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 2020. 16(11): p. 2594-2600.

19. Ali, I. and S. Hamid, Implications of COVID-19 and “super floods” for routine vaccination in Pakistan: The reemergence of vaccine preventable-diseases such as polio and measles. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 2022. 18(7): p. 2154099.